And finally… crack the case

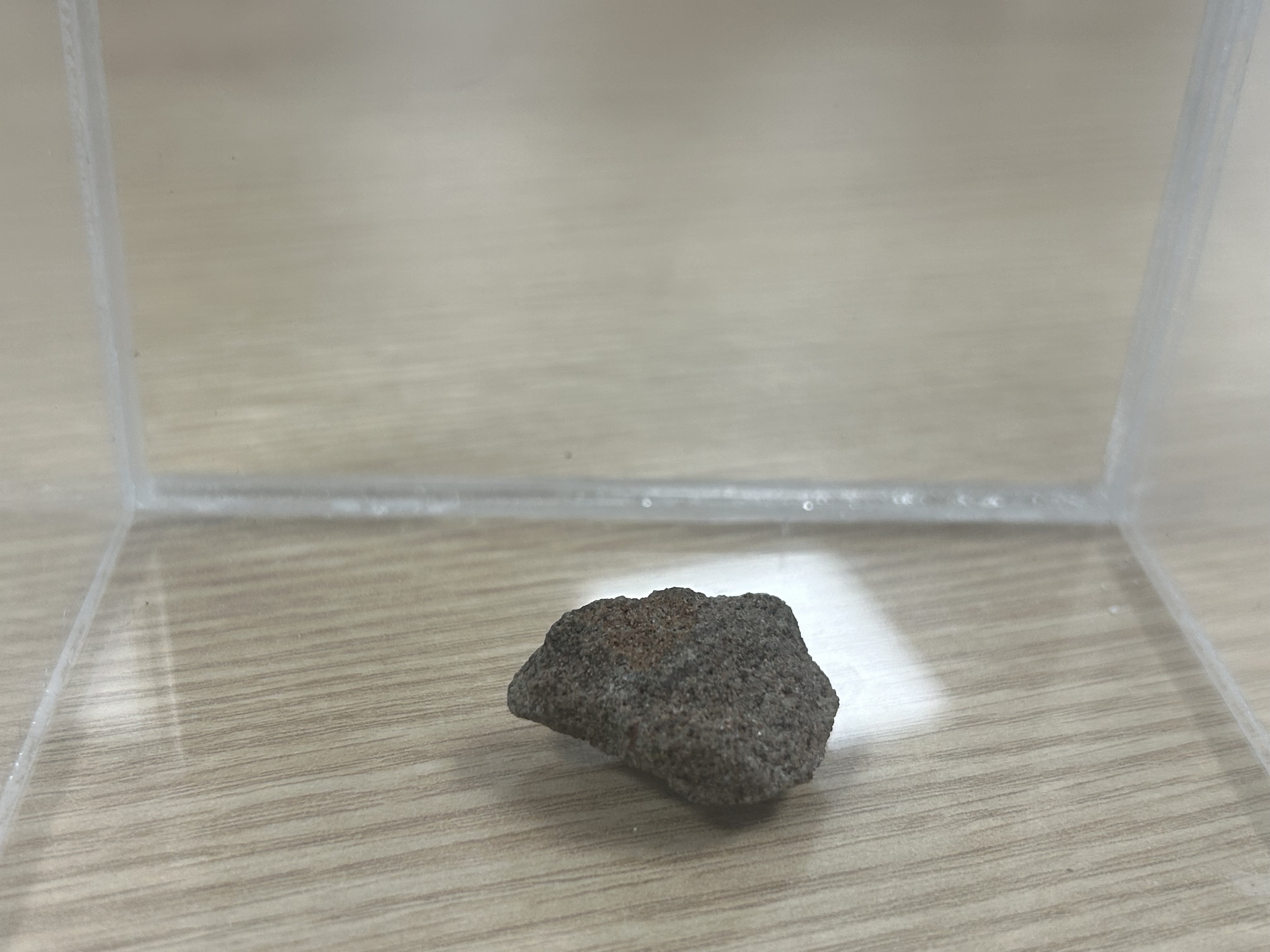

A fragment of the Stone gifted to Queensland Museum in Australia (Queensland Museum, photographer Peter Waddington)

New research led by the University of Stirling has revealed the existence and fate of many fragments of the Stone of Destiny, notably those which were secreted away after the ancient artefact was taken from Westminster Abbey by a group of Scottish nationalist students early on Christmas morning 1950.

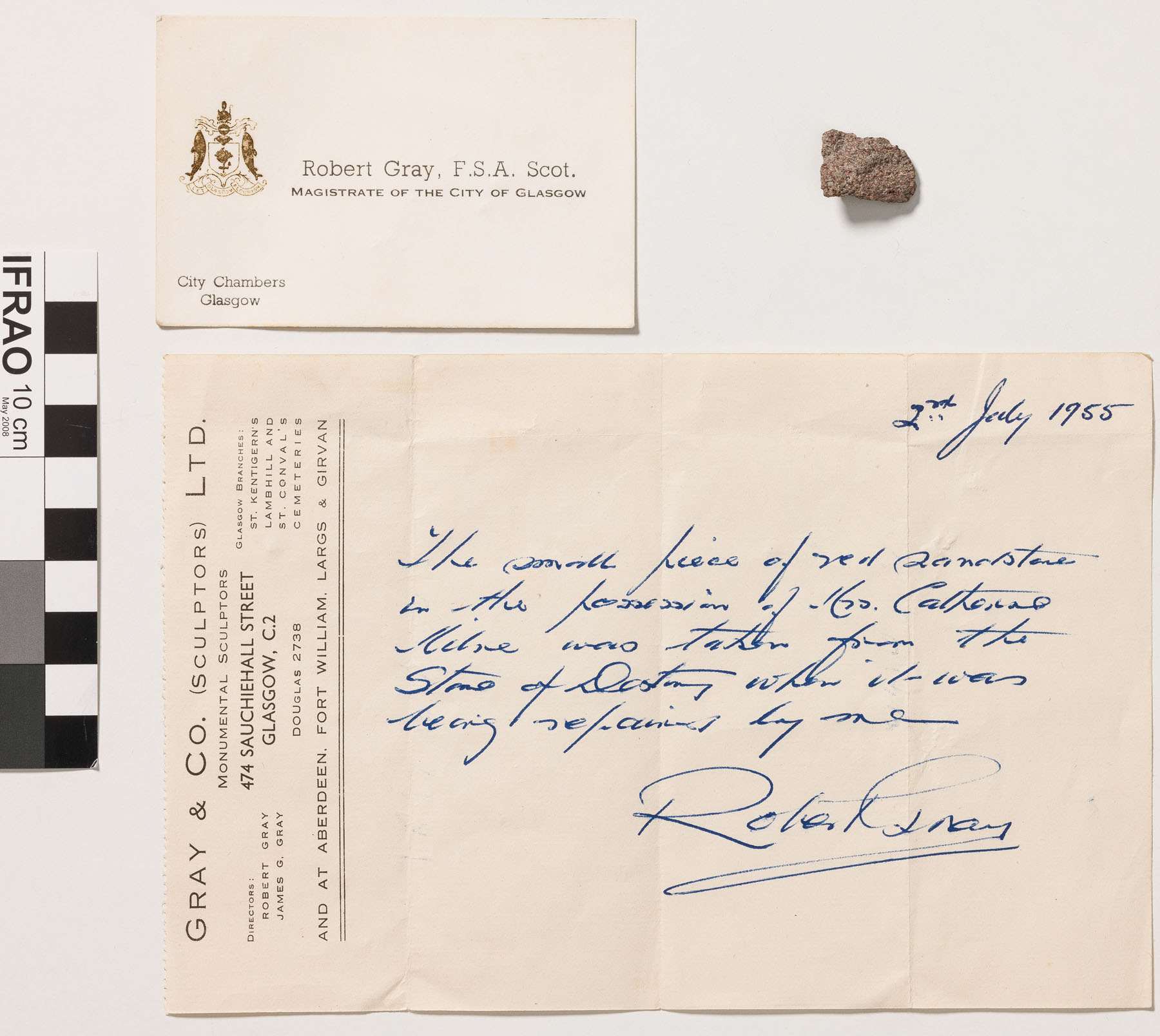

The Stone split in two along a historic crack when it was dropped during its clandestine removal. Many fragments were created during a crude repair overseen by monumental sculptor and Liberal politician Robert (Bertie) Gray, shortly before the Stone was left for the authorities to collect at Arbroath Abbey in April 1951.

Gray carefully numbered and curated 34 fragments and gifted these and further unnumbered fragments to family members, trusted political friends, nationalist politicians, and journalists at home and abroad, usually along with a letter confirming their authenticity. Fragments have been handed down by families and friends as treasured heirlooms, some encapsulated in items of jewellery.

Professor Sally Foster, of the University of Stirling’s Faculty of Arts and Humanities, has discovered the existence of this body of fragments, only one of which was officially recognised when she began her research, and carried out a rigorous study of the fragments which transforms understanding of the history of the Stone of Destiny.

Professor Foster’s extensive detective work to uncover the stories of the fragments has involved newspaper and archival research, liaison with collection curators and institutional experts, and ethnographic work, including interviews.

A fragment of the Stone which was previously bequeathed to the SNP (SNP, photographer Ross Colquhoun)

The lives of several fragments are traced, some of which were gifted to SNP politicians, including the late former First Minister Alex Salmond and two former MPs, and one fragment which travelled halfway across the world to Australia and is stored in a museum.

In a new research paper, Professor Foster also offers a novel theory about a modern inscription on the underside of the Stone which has perplexed experts.

The earliest origins of the Stone of Destiny, or Stone of Scone, are unclear. It was certainly used in the inauguration of Scottish kings from 1249, until Edward I of England seized it in 1296 and subsequently gifted it to the Shrine of St Edward the Confessor at Westminster Abbey.

Professor Foster said: “This is not just any stone. When Scottish nationalists manhandled it out of the Coronation Chair and secreted it away from London’s Westminster Abbey on Christmas morning 1950, this caused the English–Scottish border to be closed for the first time in 400 years, because, since the fourteenth century, nearly all English, later British monarchs, sat over the Stone during their coronation, in an act that symbolised the subjugation of the Scots.

“The use of the Stone in the recent coronation of King Charles and the Stone’s move to a permanent home in the acclaimed Perth Museum has stimulated new historical and scientific studies, however the existence and significance of a diverse, dispersed body of small fragments of the Stone has been overlooked.

A fragment of the Stone gifted to Queensland Museum, with its certificate of authenticity. (Queensland Museum, photographer Peter Waddington)

“Since my findings started to emerge, many members of the public have contacted me with their family’s knowledge of credible Stone fragments, often accompanied by supporting evidence – but there are many gaps yet to fill.”

The theft of the Stone, and the accidental damage, did not lead to criminal prosecutions because it was decided it was not in the public interest, and the authorities have not sought to prosecute those known to be in possession of fragments. The holder of a fragment and accompanying letter – now owned by Historic Environment Scotland – that came to public attention in 2018 was not prosecuted, and nobody associated with the fragment that was ultimately donated to Alex Salmond has been prosecuted.

However, the Stone remains a politically charged artefact – Lord Forsyth of Drumlean, the Conservative Secretary of State for Scotland who brought the Stone back to Scotland in 1996, has previously asserted that the MacCormick fragment gifted to Salmond was “stolen property…obtained as a result of a criminal act”.

Bertie Gray was the right-hand man of John MacCormick, who led the National Covenant movement that sought home rule for Scotland in the 1950s. MacCormick’s son gifted his mother’s fragment to Alex Salmond in 2008. Subsequently displayed at SNP headquarters, the MacCormick fragment was passed to the Commissioners for the Safeguarding of the Regalia in 2014 and a decision on its future home is awaited.

Gray passed fragments to politicians of many persuasions, reflecting the all-party, non-party character of the post-war home rule movement in which he and his colleagues were so active. The character of this movement seeking greater independence for Scotland was very different from today, and the fragment journeys can illuminate this. Professor Foster’s paper provides details of nationalist politicians who had fragments. These include Winnie Ewing, who wore a locket containing a chip when interviewed on television by David Frost in 1967, and who spoke of her desire to be arrested for being in possession of “stolen property”, and Margo MacDonald who was gifted a fragment by Gray after she won the Govan by-election in 1973.

Professor Sally Foster, University of Stirling

The research also sets out the story of a fragment which was gifted to a visiting Australian tourist by Gray. On her death in 1967, the family donated the fragment, accompanying letter of authentication and Gray’s business card, to Queensland Museum. Meanwhile, Canadian journalist and Calgary Herald editor Dick Sanburn mounted his behind his desk.

Closer to home, one fragment was enshrined in a silver brooch, while another was wrapped in tissue paper and placed in a Bluebell matchbox, locked in a safe at a family home in Bannockburn before being buried with its keeper.

Professor Foster said: “With the likely perception of the fragments as being stolen property, few people opted to brazenly flaunt and taunt with their possession, except for some politicians.

“Families cared for them, emotionally and physically, and we can also trace the progression of fragments to valued heirlooms.”

In the paper, Professor Foster has also suggested an origin theory for the Stone’s mysterious and modern ‘xxxv’ inscription. “I believe Gray, having gathered the 34 fragments, applied the xxxv as part of his finishing touches to the Stone’s repair - the fragments plus the Stone equals 35,” said Professor Foster. “He used Roman numerals because these are easier to scratch into stone and, as a mason, he would have been familiar with historic masons’ marks. He had the rare and almost unique opportunity to access the underside of the Stone, he had the means, he had the sense of humour, and the number 35 would only have been meaningful and significant to him.”

After the Stone returned to Scotland in 1996 it was displayed at Edinburgh Castle and an audio tour told visitors of the dramatic event that saw the Stone split in two. The immersive presentation that visitors now experience at Perth Museum, before they see the Stone, does not mention that the Stone broke into two pieces in 1950. However, visitors can clearly see the repaired crack when they have their close-up moment with the Stone, which can offer a prompt for museum staff to tell the wider story.

Professor Foster has said the cracking of the Stone and the stories of the creation and distribution of its chips – and copies of them – are essential elements when seeking to understand the Stone’s contemporary meanings and significance.

She added: “There is an unparalleled opportunity for future ethnographic work with the families that have come forward, to generate a rich understanding of the history and social value of these fragments, and what they add to our understanding of Scottish and British society. Indeed, it is desirable to collaboratively co-create a future for their fragment stories.”