And finally… National Gallery of Scotland unveils original plan for basement swimming baths

A design for the proposed National Gallery and Academy Buildings, the Mound, Edinburgh, Thomas Hamilton, 1850 (©National Gallery of Scotland)

Marking 175 years since Prince Albert laid the foundation stone of the National on 30 August 1850, the National Galleries of Scotland has shared its fascinating original building plans.

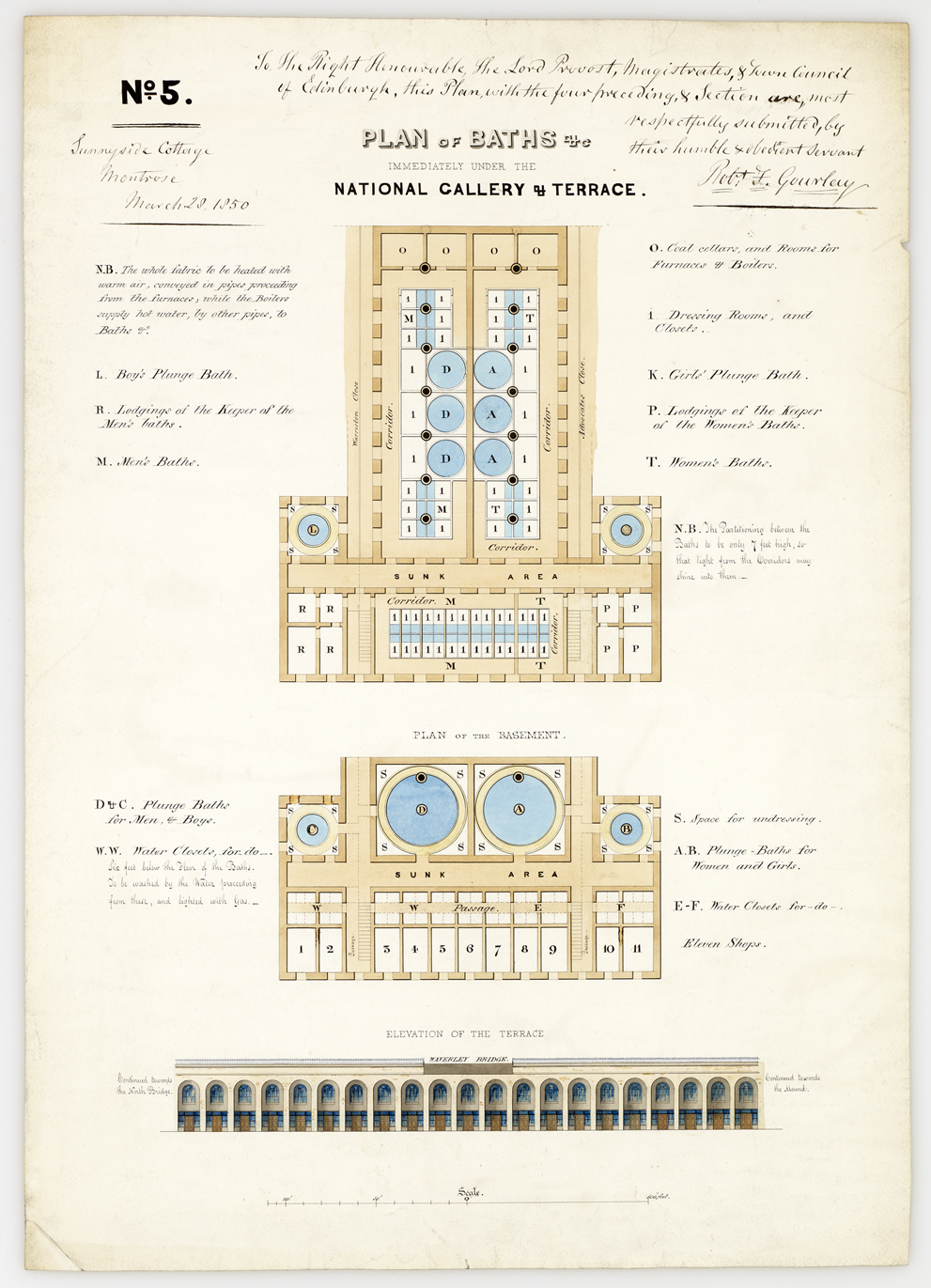

The National is an iconic part of the Edinburgh cityscape we know today, but the building itself could have been very different! One plan in particular by Robert. F. Gourlay from 1850 even shows underground baths and plunge pools incorporated beneath the gallery.

The drawing, held in the Historic Environment Scotland collection, shows the elevation of the terrace and plan of the basement, the same area where the National Galleries of Scotland opened the Scottish galleries at the National in September 2023.

You might be right in thinking that the condensation from swimming baths would not work well in an art gallery, but it was considered during the initial planning phase for the building. The plan shows separate male and female plunge pools, baths and dressing rooms, as well as ‘lodgings for the keeper of the women’s and men’s baths’. The male and female areas would be separated by a 7ft wall and all the pools would be heated.

This is just one of many plans that were created ahead of the building of the National, alongside designs by the likes of Royal Scottish Academy treasurer, Thomas Hamilton. It was Scottish architect William Henry Playfair who was eventually commissioned to prepare final designs for the iconic National building we know and love today.

Visionary proposal for the National Gallery of Scotland, The Mound, Edinburgh, William Henry Playfair, 1845 (©National Gallery of Scotland)

Playfair’s building - like its neighbour, the Royal Scottish Academy, also designed by him - was designed in the form of an ancient Greek temple. More than any other architect, Playfair was responsible for Edinburgh earning its reputation as ‘The Athens of the North’.

However, it took nearly five years to officially appoint Playfair as the architect following arguments between the members of the Board and the Royal Scottish Academy around what the building should look like. Others also believed it shouldn’t be built at all and would only destroy the natural beauty of the city centre. During this limbo period, many architects drafted their own suggestions for how they envisioned Scotland’s national gallery, including swimming baths.

Even once appointed, Playfair’s original plans differed from the building we recognise today. Originally, he set to build towers at the corners of the transverse central block, but these were abandoned during the project due to financial concerns. In fact Playfair was instructed by the Treasury to keep any kind of ornament to a minimum, because of financial stringency.

The concerns around cost weren’t the only restrictions put on Playfair’s design. He also faced town planning concerns. The council requested that Playfair ensured that the building blended into its naturally beautiful setting and did not detract from the rugged grandeur of the Castle Rock. In fact, the lack of grandeur left Lord Rutherford, a member of the Board and leading champion of the Royal Scottish Academy, to say ‘I feel sure that the architecture of this building will be too simple and pure to captivate the multitude, but I am certain I follow the right path in what I am doing and so am content.’

By 1850, the Treasury were so intent on speeding up the execution of the building that Playfair was permitted to begin work before his contract drawings were completed. However, this encountered its own issues when the Board found its hand forced in the matter of the foundation ceremony. The Lord Provost of Edinburgh, Sir William Johnstone, issued a personal invitation to Prince Albert during his presentation in London.

Drawing showing elevation of the terrace to Waverley Bridge and plan of the basement for proposed baths below the National Gallery, Robert F Gourley, 1859. (©Courtesy of HES/City of Edinburgh Council)

The Prince was incredibly keen to attend and even suggested that the Royal family would break their long journey to Balmoral at Holyrood. However, this left only a few weeks to finalise plans for the ceremony and posed a certain embarrassment since the foundations had not even been cut. This massively expedited the process and by August 30, 1850, Edinburgh society gathered to witness the laying of the foundation stone, followed by celebrations.

The National opened nine years after the first stone was laid, with Prince Albert giving a moving speech in which he hailed the Playfair-designed building as a “temple erected to the Fine Arts”. The building was officially opened on 24 March 1859. When the National was first opened to the public it had later opening hours on Saturday and Wednesday evenings so that working people could have the chance to view the national art collection. The original founders of the National gallery seemed to agree with what we know now - that art can transform lives by supporting health and wellbeing, self-expression and social skills.

Anne Lyden, director-general of the National Galleries of Scotland, said: “It is fascinating to look back on these old plans from 175 years ago and see where we started and where we are now. While the building stands true to its original design on the outside, we have continued to adapt inside, making Scotland’s world-class collection of art more accessible than ever before. We continue to hold those ideals of the original founders, that art can be transformative to people’s health and wellbeing. We put this at the heart of everything we do, with the galleries free to visit 7 days a week and ensuring we make art work for everyone.

“We also continue to grow the visitor experience at the National. In 2023 we opened the Scottish galleries at the National, transforming the visitor experience with 12 new breathtaking accessible spaces dedicated to showcasing the very best historic Scottish art. Whether exploring the galleries with friends, stopping off in the café, or entertaining the family with new trails, audio guides and events, there is something for everyone to discover at the National… Although maybe not swimming pools.”